Source: Proceso Magazine, Mexico 2017

Earthquakes are horrible events:

the ground where we stand—the one safety we take for granted—shakes under us. Even mild quakes leave a mark on those who live them. Especially in Mexico. Particularly in Mexico City and central Mexico.

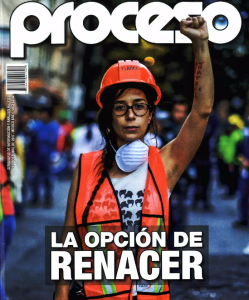

A powerful seism shook central Mexico on September 19, 2017. The known death toll is 369. Mexico City and the neighboring states of Morelos and Puebla suffered great damage. The epicenter of the quake was inland, and not in the Pacific Ocean as most of Mexico’s seism originate. An added cruelty to the event, it coincided with the 32nd anniversary of the 1985 quake, which was 30 times more powerful and several times deadlier than this year’s. Mexicans showed their best face in front of the adversity.

This time, as in 1985, the response of the civil society to the quake to the #19S (September/19) was spontaneous, powerful and heroic, with people of all walks of life organizing themselves to dig in collapsed buildings to rescue the survivors. Massive human chains removed and discarded cement and rubble, tirelessly. Small hardware store owners donated their inventory to the volunteers so they could dig and drag. Tamales vendors gave food away to the unexpected heroes who participated in the task.

Students—from public and private schools and universities, working hand–in–hand—improvised donation centers and delivered food and supplies in bicycles; truckloads of help were sent from every corner of the country.

Even rescue dogs became unexpected heroes: Frida, Evil and Eco saved lives and lifted the spirit of a nation–#TodosSomosFrida became a trending topic in Twitter Mexico.

Mexicans abroad helped too, with money and in kind. 27 countries have assisted too, with money, supplies and in some cases, sending rescue teams too.

During the first hours after the event, the reaction of the Federal and local governments was inadequate; then the professionals of disaster relief, the Mexican armed forces, deployed their troops and worked side by side with the many volunteers.

Professionals have contributed too: engineers evaluate the habitability of damaged buildings, for free; doctors and nurses were natural first responders, whether they were on duty or not. Lawyers are doing their part:

- Centro Mexicano Pro Bono, a non–profit where Appleseed, the Mexican Bar of Attorneys and others collaborate, published a legal guide for the victims of the seism, and are providing free consultations on issues as tenancy law and real estate.

- The Illustrious and National College of Lawyers, Universidad Panamericana—my alma mater— and the College of Notaries are offering free legal advice

- A group of activists, academics, businesspersons and lawyers, led by attorney Luis Pérez de Acha, filed a criminal complaint for manslaughter and fraud against public officials and the builders of some of the complexes that collapsed. Corruption is many times on the background of most problems and tragedies in Mexico: some of the buildings that fell were apparently built with lesser quality materials, others had illegal billboards, extra floors or, in one instance, a heliport that lacked the proper permits. Mr. Pérez de Acha and others are putting pressure on the Attorney General of Mexico City to investigate.

- Hundreds of lawyers are helping pro bono in a smaller scale

Mexico stands tall. I feel proud to be a Mexican. We shall overcome the adversity. And to all who helped: GRACIAS!

A los rescatistas, brigadistas, voluntarios…

y a toda la gente chingona que ayuda:GRACIAS 🙌 🇲🇽 pic.twitter.com/dxxMKIUMEK

— pictoline (@pictoline) 20 de septiembre de 2017